9.16.2006

Alzheimer's Linked to Rising Ocean Temperatures?

>

A toxin associated with Alzheimer's disease and related ailments has been found in cyanobacteria, sometimes called blue-green algae, collected from around the world.

Based on research by Hawaii scientists, it is providing what may be the first indication that different cyanobacteria produce the same toxin. It also is raising the possibility of a potential threat to public health.

Researchers are recommending that public health agencies monitor waters that can have blooms of blue-green algae that can produce the algal neurotoxin, B-N-methylamino-L-alanine, or BMAA, which can affect the human nervous system.

"As rising global temperatures trigger more blooms of cyanobacteria in the planet's oceans and rivers, the health consequences of neurotoxins such as BMAA should be monitored," the scientists said in a report in the "Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences."

In the research, Ethnobotanist Paul Allen Cox of Kauai's National Tropical Botanical Garden led a team of researchers that chased down an intriguing link between cyanobacteria and a class of apparently related nervous system diseases that include Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, also known as ALS or Lou Gherig's disease.

Cox was looking into neurological disease among Guam natives. Those suffering from the disease had high levels of BMAA in their brain tissue, and many of those affected ate a traditional diet that included fruit bats. In tracking down the diet of the fruit bats, Cox and his team found the animals ate the seeds of cycad trees, and that cyanobacteria in the roots of the trees produce BMAA.

"We have recently discovered that potential human exposure to BMAA extends far beyond Guam," Cox said.

Researchers found that a small sample of people who died as a result of Alzheimer's disease in Canada — where there are no fruit bats or cycads — also had BMAA in their brain tissue. There were indications of similar patterns in people in parts of Japan, where there are cycads but no fruit bats.

Cox said the key seems to be neither the cycad nor the bat, but the cyanobacteria. "It's like a detective story," he said.

Scientists have long known that cyanobacteria can produce dangerous compounds, but this appears to be the first indication that very different cyanobacteria can produce the same poison.

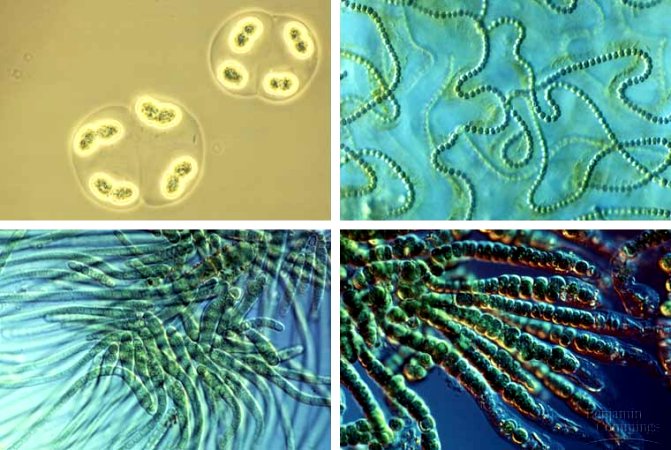

Cox and his team of researchers looked into cyanobacteria samples from very different environments and found that in each of the five major types of these blue-green algae, some species produce BMAA.

Often, there is not much of the neurotoxin and it may take some kind of process to "biomagnify" the poison. Fruit bats in Guam may have done that by eating a lot of cycad seeds. A new question is what might be biomagnifying BMAA in other environments.

Cyanobacteria are among the oldest forms of life on the planet. They are single-celled organisms that behave like bacteria, but can conduct photosynthesis like plants. They generally live in water, but also can live inside plants.

Also contributing to the research were cyanobacterial experts Robert Bidigare and Georgia Tien at the University of Hawai'i at Manoa, Cox said.