7.16.2005

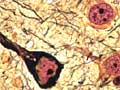

Alzheimer's Research

>

Here is a fascinating new development in Alzheimer's Research

University of Minnesota researchers have figured out a way to reverse memory loss in mice with dementia. The discovery could lead to new treatments for Alzheimer's disease in humans. The findings are published in the latest edition of the journal "Science."

Minneapolis, Minn. — In the study, mice were genetically altered to develop a rare form of dementia found in humans. To do that U of M researchers used a special gene, known as a transgene, that contained a mutant form of a common protein called tau.

Tau is one of two proteins widely associated with Alzheimer's disease. The scientists then created a way to turn the defective tau protein on and off using a common antibiotic.

When the mice were a month old, researchers tested their memory capacity for the first time in a water maze. Lead author of the study, Dr. Karen Ashe, says the maze consisted of a small pool with a hidden platform that was submerged about a half a centimeter below the surface.

"Mice are really good swimmers, but they don't like to swim," says Ashe. "So they're motivated to find the platform."

The platform was kept in the same place until the young mice learned where it was located. Then researchers removed it and measured the percentage of time that the mice spent looking for the platform in the correct location in the pool.

"Even though this test seems like a very simple test, it's actually fairly complex for a mouse," says Ashe. "And it tests a part of the brain that really is critical for initiating and consolidating memories."

Since the mice were only a month old, their dementia wasn't noticeable yet and Ashe says they performed well in the maze. She says they spent about 50 percent of their time in the correct quadrant of the pool as they searched for the missing platform.

But as the mice aged and their dementia progressed, their success rate dropped significantly, just as Ashe thought would happen.

That's when researchers decided to shut off the defective tau transgene. Then, they tested the mice again. The findings were much better than expected.

"We were quite surprised with the results of the experiment, because we had expected that we would halt the progression of memory loss," says Ashe. "But we actually restored memory in these mice." Entire Story